Title: Japanese Vice Minister of Defense Suzuki Atsuo Delivers Remarks on the US-Japan Alliance

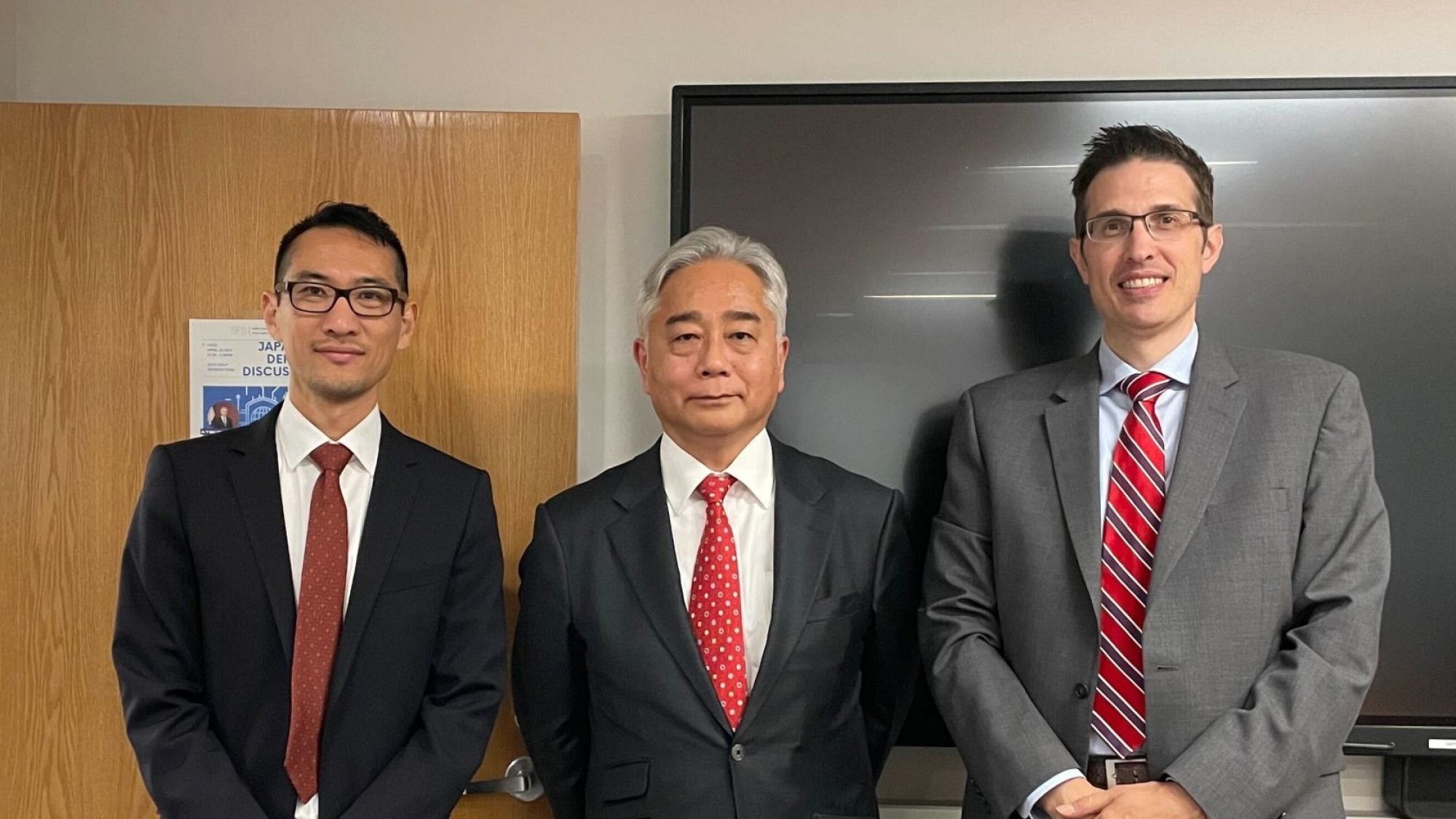

Earlier this April, Japanese Administrative Vice Minister of Defense Suzuki Atsuo spoke to Georgetown students and faculty as part of a critical diplomatic visit to D.C. to reaffirm the US-Japanese alliance with American military and diplomatic officials. After studying at the Walsh School of Foreign Service from 1989 to 1990, he returned to campus to sit down with MASIA Director Yuhki Tajima, Dr. Jeffrey Hornung, and other Georgetown faculty and students in his capacity as the Japanese Vice Minister of Defense.

In his appointment, he directs the planning and execution of Japan’s defense policy as well as the overseeing the day-to-day operation of the Ministry of Defense. Prior to his appointment, he served as the Commissioner of Japan’s ATLA (the Acquisition, Technology & Logistics Agency), a part of the Ministry of Defense, where he was responsible for managing Japan’s defense equipment policy. The Vice Minister’s remarks as delivered during the event are as follows:

Hello everyone. Thank you for the kind introduction. I’d like to begin by expressing my sincere appreciation to Dr. Hornung, Dr. Tajima, and to all those involved in organizing today’s event. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to speak with you today.

It’s great to be back here after more than 30 years since graduating. I studied at Georgetown from 1989 to 1990. I first enrolled in a fellowship program at MSFS; and later switched to the National Security Studies Program and concentrated in national security. It was a vigorous program and I remember many late-nights working furiously to finish the assignments. It was a great experience, which I cherish to this day.

I’m honored to be invited back and to be able to speak with you today in my capacity as Japan’s Vice Minister of Defense.

As Vice-Minister of Defense, I am in charge of planning and executing Japan’s defense policy and overseeing the day-to-day operation of the Ministry of Defense. Prior to this, I was the Commissioner at ATLA, the Acquisition, Technology & Logistics Agency, which is situated under the Ministry of Defense and is in charge of managing Japan’s defense equipment policy.

I wish to share with you today my thoughts on the security environment surrounding Japan; on the role of the Japan-U.S. Alliance in ensuring global stability; and on the outlook of Japan’s defense policy.

Let me begin by asking you a question. Which country do you think hosts the largest number of U.S. troops abroad? Do you think it is Germany or somewhere in the Middle East or South Korea?

The answer is Japan. Approximately 55,000 U.S. troops are stationed in Japan — the largest number in the world. There is even a base for U.S. naval fleets situated in Japan.

Over 50,000 U.S. servicemembers currently reside on the opposite side of the pacific. They are working tirelessly to protect the peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific. If we include their family members, a greater number of people are contributing to the stability of the region. This is made possible through the stationing of U.S. troops in Japan.

The Japan-U.S. Alliance is a time-proven, resilient alliance, that has played an indispensable role in securing regional and global stability for many decades. This is a fact that I firmly believe will not change in any foreseeable future.

The U.S. is Japan’s one and only, vital ally. I personally was lucky to have had the experience of living in the U.S. twice. During my stay in the U.S., the international environment underwent some historical changes.

First time I lived in the U.S. was during my time at Georgetown. Back then, majority of my classes were focused on the Soviet Union — Soviet Foreign Policy, Soviet Military Doctrine, and so on. At the time, “WTO” stood for Warsaw Treaty Organization, not the World Trade Organization. There were hardly any classes on China, and no one at the time imagined that NATO would eventually expand.

The collapse of the Berlin Wall happened during my studies at Georgetown. Subsequently, upon returning to Japan a year later, the Cold War ended. What I learned at Georgetown became a page in history. The world entered an era of great power cooperation and an expanding free and open rules-based international order was underway — as described in Francis Fukuyama’s “The End of History.”

Second time I lived in the U.S. was when I attended the National Defense University from 2000 to 2001. The beginning of the 21st century witnessed the emerging threats of terrorism and so began the war on terrorism. Upon finishing my studies at NDU, I returned to Japan in June 2001.

As it so happens, I was on a plane flying over Washington D.C. when 9/11 occurred. There were big events slated to take place in New York, Washington D.C., and San Francisco respectively, to celebrate the Japan-U.S. Alliance. At the time, I was flying in a plane headed to Washington Dulles Airport from Tokyo. The plane was half an hour away from landing at Dulles airport when 9/11 occurred, and was diverted to Detroit. Needless to say, all the anniversary events were cancelled.

As you know, since after 9/11 and the war on terrorism, there has been a historical shift in global power balance and an increasingly intensifying geopolitical competition. The rules-based international order is now facing a grave challenge. Particularly in the Indo-Pacific region, a historical shift in power balance is taking place. In areas surrounding Japan, aggressive military buildups including that of nuclear and missiles are taking place at an alarming high pace; and attempts to unilaterally change the status quo are intensifying.

Moreover, we are seeing a number of gray-zone situations whereby the distinction between war (conflict) and peace (cooperation) is becoming increasingly ambiguous. Gray zone situations involve activities such as 4 transboundary cyberattacks targeting critical civilian infrastructure; and information warfare by the constant dissemination of disinformation; among others. In addition to this phenomenon, the widening scope of national security to include areas such as economy and technology — is also making the line between military and non-military quite ambiguous.

How we fight in war has also changed significantly in recent years — as seen in Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. New ways to fight a war include, for instance, information warfare by use of false flag operations; massive attacks by use of high-precision missiles that includes both cruise and ballistic missiles; hybrid warfare by use of unmanned assets to conduct rapid, multi-tier attacks in space, cyber, and electromagnetic domains. In addition to these types of operations, Russia has recently threatened the international community by publicly stating the possible use of nuclear weapons.

With the apparent rise of new types of warfare, it is critically important that we build a defense posture that includes the necessary capabilities to counter both existing and new security challenges.

We cannot rule out the possibility of a serious contingency occurring in the near future in the Indo-Pacific, particularly in East Asia — one that could potentially undermine the foundation of the post-war international order.

If such contingency was to really occur — the fallout would be catastrophic. The damage it would cause not only to the region but to the entire world are immeasurable. Thus, we must make all efforts and take every possible step to prevent the occurrence of such contingency.

Japan is situated in the forefront of such possible situation; and it’s no exaggeration to say that Japan’s national security is directly linked to the peace and stability of the region and of the world.

Last year, with the aforementioned possible situation in mind, Japan renewed the following three strategic documents — National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Program; which set forth a transformational change in Japan’s defense policy. The release of these documents was welcomed and highly praised in both Japan and abroad. I’d like to briefly explain the reason behind this and its background.

Japan and the U.S. signed the first security treaty on the same day as the conclusion of the Treaty of San Francisco in September 1951. This was shortly after the beginning of the Cold War and the first time the East and the West openly locked horns in the Korean War. Subsequently in 1954, Japan established the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) and built up defense capabilities that were minimally required for self-defense purposes. In 1960, the first security treaty was revised and the current Japan-U.S. Security Treaty was established.

In the midst of a staggering domestic economy and reduced tensions between the East and Western bloc due to détente, the Japanese public took a harsh stance towards an increase in any defense-related budgets and defense capabilities. In 1976, Japan established the first “National Defense Program Guidelines,” which was based on the “basic defense force concept.” This concept set forth the course of Japan’s defense posture that allowed for a minimum defense force required to maintain Japan’s sovereignty, and a maximum threshold of 1% of GNP for defense-related expenses. Moreover, a policy concerning overseas transfer of defense equipment was introduced that effectively banned all equipment transfers to any country.

The aforementioned policies determined the course of Japan’s national security for many following years. Meanwhile, the security environment surrounding Japan has drastically changed over the years. And in recent years, the surrounding situation has become so severe that national security is no longer an issue that can be put on the backburner.

So we had to ask ourselves — “can we really afford to remain the same whilst neighboring countries bolster their military buildup? The answer was “no” — that in order to protect the Japanese people, we need to harden our defense posture. This was backed by a significant change in threat perception.

Japanese public opinion towards national security has changed significantly over the past several years. The trend is evident in results shown in national defense-related polls conducted once every three to four years. The numbers show that a majority of Japanese regard national security as a high priority.

For instance, in the last poll (conducted in January 2018), a question was asked regarding the size of the SDF — only 29 percent responded that the number of SDF members should be increased. However, in the most recent poll \(conducted between November and December 2022), this percentage increased significantly to 42 percent.

Japanese public perception towards the SDF is quite positive. This is based not so much on defense activities, but mainly due to the SDF’s disaster relief operations and the SDF’s contribution in COVID-19 vaccinations. However, in last year’s poll, 78 percent of the respondents said that they expect the SDF to play a role in securing Japan’s national security – up 17 points from the previous poll.

Due to the country’s dark history during WWII, education on defense and security studies are not typically offered in schools in Japan. The Japanese academia has also been rather hesitant to take part in military-related research. Major universities offer programs on international relations, but generally do not offer courses on “national security” nor “war studies.”

Personally speaking, I learned national security for the first time at Georgetown. Yet, we may expect some changes in this area as well. In last year’s poll, 89 percent of the respondents said that national defense should be taken up in the country’s education. It goes without saying that without education or knowledge on defense, it would be near to impossible to adequately defend one’s own country.

As aforementioned, Japanese public opinion towards national security has dramatically changed over the years. In terms of public opinion towards the Japan-U.S. Alliance — 90 percent responded that the alliance contributes to Japan’s peace and security, which is another significant increase from 78 percent from the last poll.

The dramatic change in public perception towards Japan’s national security is due mainly to the significant change in the security environment surrounding Japan and advancements in technological innovation. The newly introduced three strategic documents reflect these changes and depart from the policies that were implemented since 1976.

The three strategic documents stipulate that Japan will increase its level of defense spending to 2% of GDP in FY2027 in order to fundamentally reinforce Japan’s defense capabilities and complementary initiatives in meeting new security challenges. Also noted in the documents is a proposal to consider revisions of the Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology, its Implementation Guideline, and other systems. While taking into account that defense equipment transfers are important policy tools in creating a desirable security environment for Japan; one of the objectives here is to allow Japan to transfer equipment to countries that have suffered aggression in violation of international law.

It’s also noteworthy that the naming of the title has changed from “National Defense Guidelines” to “National Defense Strategy.”

There are two key terms when discussing Japan’s defense policy in the new era. First is the buildup of a comprehensive defense posture; and secondly, strengthening the Japan-U.S. Alliance as well as deepening cooperation with like-minded countries and others.

Until recently the general thinking has been that national security is achieved by efforts in defense and diplomacy. Yet, in recent years, we have seen that no nation can secure peace alone. The SDF on its own cannot prevent transboundary cyberattacks that are occurring from all parts of the world.

Furthermore, without a stable defense production and technological bases, Japan will not be able to compete at an equal footing with other countries nor cooperate with them. We believe that it is now necessary to combine the whole power of the country including economic power, technological power, informational power, and military power to protect Japan’s national interest through a comprehensive and strategic approach.

In other words, Japan will strengthen not only the capabilities of the SDF but will also take a whole-government approach and make use of all branches of the government to secure Japan’s national interest. The government will also work closely with the civilian sectors in achieving this objective.

As we recently saw in Finland and Sweden’s bids to join NATO — no single country can protect its sovereignty anymore. Thus, defense cooperation with our ally the U.S., like-minded countries, and others is crucial in meeting today’s new security challenges. In fact, we must not only cooperate but work together and collaborate with the U.S., like-minded countries, and others to secure regional and global stability. As stated in the three security documents, Japan will strengthen and accelerate collaboration with our ally the U.S., like-minded countries, and others.

The three strategic documents have set the course for Japan’s national security in the coming years. I had the privilege of being involved in the development of these documents in my capacity as Vice Minister of Defense and in my previous capacity as Commissioner for the Acquisition, Technology & Logistics Agency. Based on this experience, I’d like to now talk on the outlook of the Japan-U.S. Alliance, and also touch upon two key areas that I believe will help strengthen the Alliance even more. Such areas are in strengthening Japan’s defense industrial base, intelligence, and informational power.

As stated in the 2022 National Security Strategy, in order to safeguard Japan’s national security, the highest priority is to be placed upon strengthening Japan’s own defense capabilities, which in effect will benefit the Japan-U.S. Alliance. As aforementioned, no country on its own can protect and maintain its sovereignty amid the increasingly tense security environment. The Japan-U.S. Alliance based on shared values is crucially important more than ever before. Bolstering the Japan-U.S. Alliance contributes to not only the security of Japan and the U.S., but to the peace and security of the Indo-Pacific region and of the entire international community. Therefore, we must endeavor to constantly update and modernize the Alliance and reinforce the joint capabilities of the SDF and U.S. Forces.

Last year, the Biden administration issued the U.S. National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy for 2022, respectively. The visions, priorities, and objectives outlined in these documents are consistent with that of Japan’s three strategic documents.

Japan is set to increase its defense budget by 1.5 times over the next five years to a total about 43 trillion yen, and then to 2% of GDP in FY2027. With such significant increases in financial resources, the government will work to quickly acquire new capabilities and enhance SDF’s operational sustainability. As Japan’s defense capabilities are reinforced, Japan and the U.S. will review the roles and missions of the SDF and the U.S. Forces to achieve greater effectiveness.

At the Japan-U.S. 2+2 meeting held earlier this year, our two countries agreed to work in bolstering ISR capabilities; to accelerate equipment and technological cooperation; and to reinforce information security and cybersecurity; among others. These efforts will deepen the scope of the Alliance and will significantly enhance our joint operational capabilities. What is important here is that Japan has widened its areas for cooperation. Japan will play a proactive role in developing tangible measures for cooperation in each of the agreed areas.

As stipulated also in the three strategic documents, Japan will work to strengthen the country’s defense industrial base. This is an area of crucial importance for the Japan-U.S. Alliance as it will help maintain supply chains of critical goods and components, and will also contribute in preventing technological leaks. There are no state-owned defense companies in Japan. In other words, the Japanese government rely wholly on private companies for the manufacture of defense equipment. Thus, Japan’s defense production base and the technological base that support the manufacturing of defense equipment play a vital role in protecting national security. The defense industry is an indispensable partner to MOD and SDF.

The war in Ukraine showed us the importance of responsive use of civilian technology in modern battlefield. The private sector has been playing a significant role in the war in Ukraine, particularly in space and cyber. Military conversions of civilian drones have achieved great success. We may go as far as to say that in modern warfare, the sooner the use of civilian technology, greater the chances of gaining superiority on the battlefield.

There is still no clear evidence that shows that AI technology has been used in the Ukrainian war. However, given recent developments in AI technology, its highly likely that AI technology will be used in battles within few years. In the so-called “next war,” the side that can successfully use AI technology may possibly gain the upper hand.

However, military organizations in general are not good at quickly applying civilian technology on to the battlefield. It usually takes a decade or two to grasp technological trends; formulate operational concept; conduct research and development; and to procure the system. Given the long time required, it might be necessary to just begin by using existing technologies. In fact, I think we’ve all experienced this but when using new functions or applications on our smartphones, we usually just go ahead and try them as oppose to contemplating over how to use the new functions. With this approach in mind, we at MOD will endeavor to find creative ways to expedite the defense buildup process.

Moving on to the next topic. Reinforcement of informational power — or more specifically, intelligence capabilities that includes swift and appropriate information sharing as well as information security, which is another basis of the Japan-U.S. Alliance. The National Security Strategy, Defense Strategy, and Buildup Plan — all refer to the reinforcement of informational power as a major pillar. In my career, I have focused on this topic from the standpoint of the Alliance.

Until recently, information was perceived as a tool that aided governments in appropriate decision-making. However, we are now in a time whereby information serves as a weapon in itself — a method to nullify the adversary’s decision-making and deter it’s actions.

Responding to integrated information warfare with special regard to the cognitive dimension is key in the modern way of warfare. Japan must reinforce its informational power. In particular, taking into account Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, responding to integrated information warfare, with measures such as the detection and analysis of disinformation, and swift and appropriate communications, can be said to be of utmost importance.

The Japanese Ministry of Defense will set in place a solid regime for responding to integrated information warfare, starting with its central intelligence agency – – the Defense Intelligence Headquarters. The DIH will play a central role in responding to information warfare. We believe that utilizing artificial intelligence, AI, will be crucial, and will be using it, for example, in the automatic collection and analysis of OSINT — open-source intelligence.

Of course, the importance of regular communication, including strategic communication, cannot be understated. When countries that share fundamental values, such as democracy, the rule of law, and basic human rights, promote a mutual narrative — it greatly contributes to regional and international stability. Japan will work in coordination with our ally the U.S. and partner countries to strategically communicate appropriate information on a regular basis. In my career, I have held various intelligence-related positions, and was an active participant in inner-circle discussions. However, as a pioneer of newage intelligence, from now on, I would like to seek opportunities to engage the public, as I am doing so here today.

Information security is crucial. Reinforcing information security is vital in preparing a response for integrated information warfare; and when coordinating with the U.S. and our partner countries. In order to protect the decisionmaking of Japan, our ally, and partners from opponents — we need a resolute security system. In addition to educating our people and improving information literacy, we will staunchly protect our information systems.

The 17th century Haiku master Basho Matsuo, who created “haiku” poem — a traditional Japanese culture that has thrived for over 300 years – advocated the principle of “fluidity and immutability” — in Japanese “fueki ryuko” — which recognizes the value of tradition, but also emphasizes the importance of incorporating new ideas.

Same can be said about national security. In today’s world, it is increasingly difficult for governments to foresee the future. Each country must thrive to achieve security and prosperity of its people. Yet, an unpredictable future may not be all bad — it could be a great opportunity to introduce new ways of thinking and to implement new ideas.

I hope everyone here today will seek a vision that is rooted in lessons learned in history, yet at the same time, is creative and future looking. I hope you will challenge yourselves to all possibilities with a positive attitude. My hope is that you will study hard, deepen your friendships, and strive to achieve your dreams.

Thank you.

Vice Minister of Defense, Suzuki Atsuo

More News

Join the Georgetown Asian Studies Program for our annual US-China Conference. This year’s theme is “A New Geopolitical Era and U.S.-China Competition” Organized by Professor Evan Medeiros, the…

The Asian Studies Program is pleased to announce the creation of the new 18-credit Undergraduate Certificate in South Asian Studies. Candidacy for the Certificate is open to all Georgetown University…

Dr. Yuhki Tajima begins his tenure as Director of Asian Studies on July 1, 2022. He succeeds long-time Director Dr. Michael Green, who is taking a leave…